Monadnock Peacemaker

the Monadnock Building

When it was completed in 1891, the 215-foot-tall Monadnock Building was the world’s tallest skyscraper. While the Chicago skyline is now dominated by much taller buildings, the Monadnock was built using a fundamentally different structural technology.

A high-rise office building exists to maximize the leasable square footage of a given piece of real estate by stacking multiple floors on top of each other. With sixteen floors, the Monadnock Building has about sixteen times as much square footage as a single-story building built on the same site. The loads acting upon it are also about sixteen times as much. In the case of the Monadnock Building, its thick masonry walls resist these forces. The issue with a load-bearing building of this type is that as it grows taller, its walls must grow correspondingly thicker to support the added weight of any added floor. There exists a threshold where building higher would no longer be worthwhile because so much of the interior would become occupied by the structurally required solid poché. Such was the case with the Monadnock Building and its six-foot-thick exterior walls.

Even as it was under construction, advances in steel technology made it practical to create a structural skeleton that concentrated a building’s loads into a frame of relatively thin beams and columns. This liberated the walls of a building from their structural responsibilities and would transform architecture for the remainder of the 19th century and beyond.

A half-century later and an ocean away, Nazi Germany had conquered most of continental Europe. In 1940 as the Battle of Britain raged in the skies above the United Kingdom, American military planners realized that, were the British Isles to fall, any bombing campaign against German targets would need to be launched from bases in North America. This would require a heavy bomber with an unprecedented range of some 10,000 miles. No such plane existed at the time and so the US Army Air Corps began developing the world’s first intercontinental bomber.

Achieving the required performance goals proved challenging with existing 1940s technology and by the time the first prototype B-36 flew, the Second World War had already ended (as Britain never fell to the enemy, the United States was able to fly from there using existing bomber designs). Although the B-36 was created to fly from North America to drop conventional weapons on Germany, its capabilities allowed it to also fly from North America to drop atomic weapons on the Soviet Union. And so while it would play no part in the world war it was designed for, it served as an important deterrent to keep the peace during the early days of the Cold War. This is why the B-36 was given the unofficial nickname of “Peacemaker.”

the B-36 Peacemaker (United States Air Force: the appearance of U.S. Department of Defense (DoD) visual information does not imply or constitute DoD endorsement)

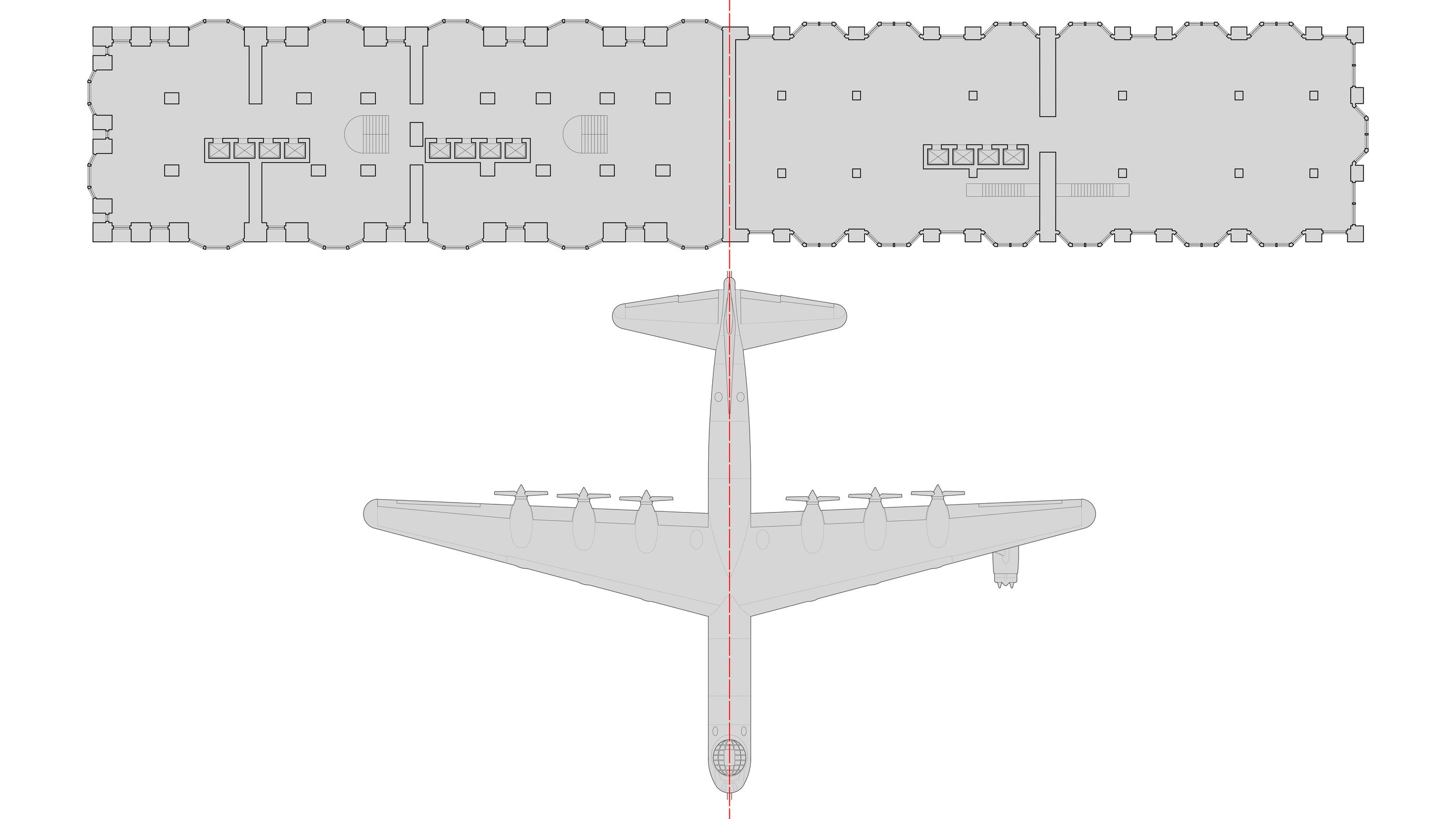

Just as the Monadnock Building was the tallest load-bearing office building ever built, the B-36 Peacemaker with its 230-foot wingspan was the largest piston-engined aircraft ever produced. And similar to how the office tower in Chicago represented the evolutionary end of load-bearing high-rise construction, the straight-wings and rotating propellers of the B-36 represented the end of the approach to bomber designs associated with the Second World War. Both the Monadnock and the Peacemaker existed at the extreme frontier of what was possible with a given technology just as that technology was rendered obsolete: jet propulsion systems redefined aircraft design in the middle of the 20th century the same way steel structural systems revolutionized architectural design at the end of the 19th century

When developers decided to add onto the Monadnock Building, they abandoned the load-bearing structure of the original building in favor of a more modern steel structural frame. Although the exterior appearance of the two halves of the building are similar, the newer addition is clad in only a thin veneer of brick (ironically, the new addition featured more traditional ornament and so appears less “modern”). These thinner walls allowed each level to have nearly 10% more leasable floor area. If the Monadnock’s Building’s southern half represents the high water mark of an old way of building, its northern half presaged how high-rises would be built moving forward. Similarly, later versions of the B-36 saw the addition of J47 turbojet engines to underwing nacelles that allowed the aircraft to increase its cruising speed from 230 to over 400 miles per hour. Like the Monadnock Building, the B-36 Peacemaker became a hybrid of the of the past and the future.

Both the Monadnock and the Peacemaker are transitional artifacts straddling the line between old and new. They simultaneously demonstrate the limits of what was while presaging what could be. The architects of the Monadnock Building and the engineers of the B-36 didn’t know what they were designing would represent the end of an era just as we don’t know if what we’re building today will be the last, greatest example of something that will be eclipsed by what is to come.

the original Monadnock Building (upper left), the later addition featuring steel structure (upper right), the original B-36 (lower left), and the later version fitted with under-wing jet engines (lower right), all drawn at the same scale